Robert Falcetti is a photojournalist and commercial photographer that uses the PhotoShelter platform to advertise his work. He kickstarted his career working for newspapers as a picture editor and photographer where he met great mentors. Working at daily newspapers taught him that one can only create strong images through fully embracing the subjects and their stories and not giving in to one's ego.

Robert is an editorial and advertising photographer whose pictures are published in national and regional magazines, and are used by advertising agencies, design firms, and corporate clients nationwide. Robert regularly is hired by the nation's most prestigious independent schools, private boarding schools and higher education clients to produce distinct imagery for admissions marketing, alumni magazines and development capital campaigns. He is available for assignment worldwide. When not traveling, he resides in the historic New England village of Plantsville, in the Connecticut Apple Valley Region with his wife and three children, a black Lab named Dixie and a Maine Coon cat.

Hi Robert, what are you working on at the moment?

Right now I’m continuing to focus my efforts on documenting the sugar cane worker communities known as Bateyes in the Dominican Republic.

Back in September 2013 the Dominican Republic’s highest court retroactively revoked the citizenship of all persons born without at least on Dominican parent since 1929. Many of these people are the migrant workers in the sugar cane industry. They are mostly Haitians or those born in the Dominican Republic of Haitian decent. Some estimates put that population at close to one million people with about half of those working on the sugar plantations. They are scattered around the Dominican Republic and reside mainly in the 500 Batey’s, the settlements and communities that developed around the sugar industry and the sugar cane plantations. The Haitian migrants usually do not have the documentation or funds to return to Haiti and those who were born in the Dominican Republic to Haitian parents have never been to Haiti in their lifetime.

Haitian migrants, the vast majority of the sugar cane workers, were first brought to the Dominican Republic to work in the sugar sector in 1919. Today the majority are undocumented workers brought into the Dominican Republic by human smugglers known as Buscones, who in some instances work as labor brokers. They work during the harvest, which takes place from December to July with about 40% of the production being done by manual labor. It has been described as a form of modern day slavery. Working on this project has really made me much more aware about the products we consume and where they or the ingredients in them originate. The healthiest and strongest workers can cut around 3 to 4 tonnallata (approx. 2,200 pounds) each in a 12-hour shift that begins at 4 a.m. A cutter can earn 120 pesos per tonnallata of cane per day, currently about $2.82 U.S. So in 12 hours of hard labor, the most productive worker will earn between $9 and $12. The cane cutters usually earn less than that though for their day’s labor. They are supposed to be paid for raw cut cane which has water weight in it. The cane is ticketed and loaded onto carts that should be weighed at the end of the day to determine the workers pay. The carts are often left overnight which allows the cane to dry out making it lighter and less costly. This lighter weight is what the sugar cane cutters are paid for. Once the sugar is taken to the refinery it is re-hydrated for processing without any loss of actual sugar content. It is estimated that the actual workers make between $3-6 per day due to the weighing. What that worker makes in a day, is what we typically pay for one bag of refined sugar in the grocery store. If we spend more time investigating where our food comes from, I’m sure many of us would be shocked at how it originates. A statistic from the U.S. Department of Agriculture states that American’s consume 80 pounds each of sugar per capita each year. That is roughly 31 five-pound bags, almost 1-ton of raw sugar cane, for each of us. One ton of sugar cane yields approximately 38 five-pound bags of refined sugar. Basic food staples like rice and beans are expensive for the cane workers. Rice costs approximately 20-25 pesos, $.65 lb., in the Dominican Republic whereas the typical American household (family of four) spends around $1,000 per month for food.

I heard a stat that claimed the energy used cutting three tons of cane per day is estimated to be the equivalent to running a marathon. I have not been able to personally verify this statistic but from what I have witnessed, it is a tremendous amount of back breaking work. The sugar cane workers do this 7 days per week.

My photos are not going to change the plight of these workers, but if a viewer pauses long enough stop and think about what is happening in them and is personally moved enough to react, perhaps in the long term it could affect change.

Do you have any formal training in photography? If not, where did you learn your trade?

Not really any formal training in photography. I had a few classes in high school and college, but most of my training as a photojournalist was learned working at daily newspapers. I have been blessed throughout my career to work with some really talented photographers who were a great influence and mentored me. During my daily news career I worked at a variety of small and medium circulation papers and a large metro daily. Prior to leaving the newspaper business in 2014 I had been a photo editor for sixteen years. Hopefully I was able to make a difference and give back as a mentor to the photographers who worked for me.

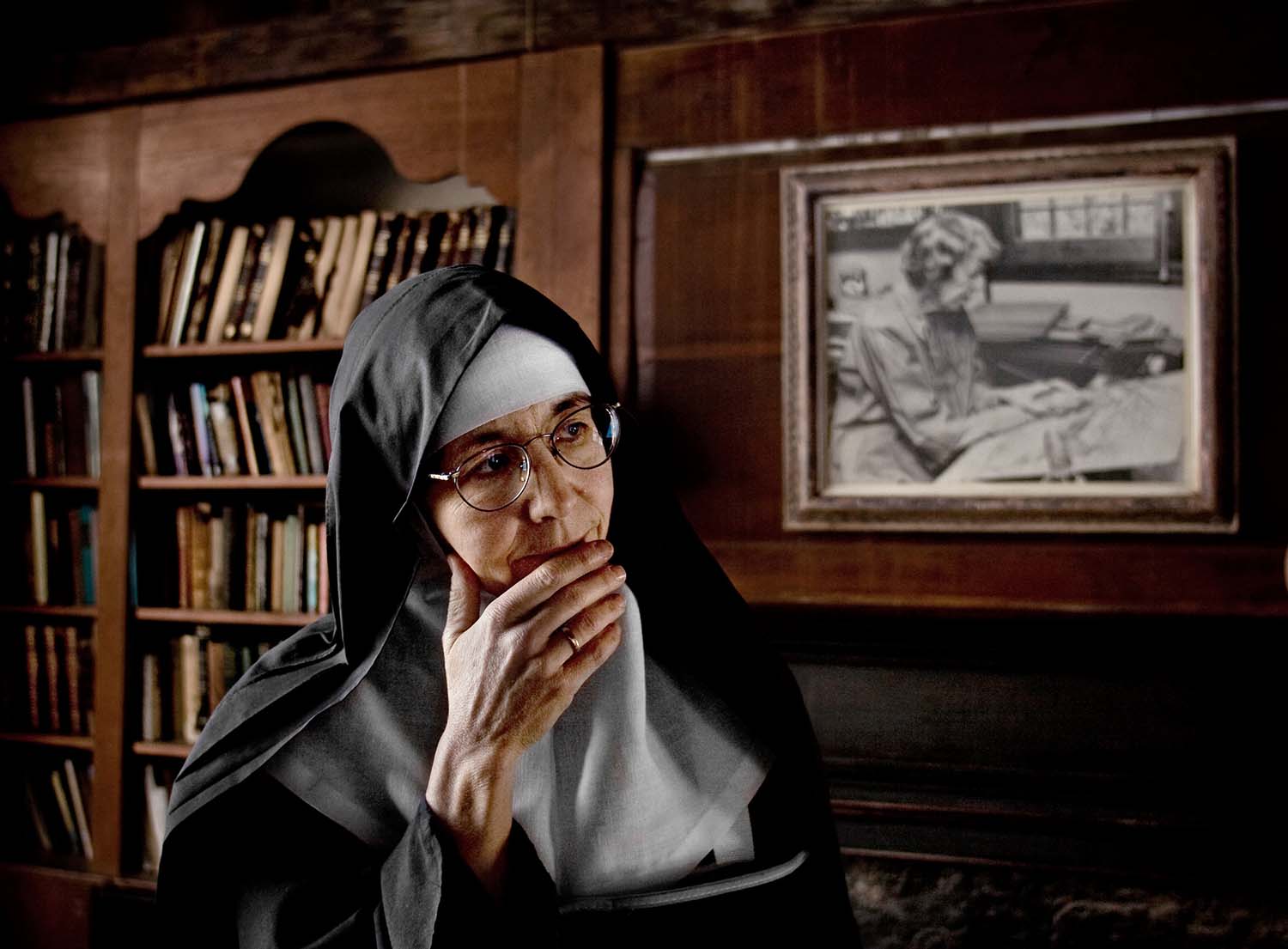

What inspired your series ‘La Vita Monastica’?

La Vita Monastica started as a one off assignment working on a story about the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Bethlehem, Connecticut. The shoot went great and I really enjoyed the location and the nuns and knew I wanted to return and make images there. It took almost a year of visits to gain the trust of the community and start to focus on a few of the unique personalities who lived there. It is a cloistered Benedictine monastery so you can’t just show up and start taking photos. Over time they invited me into their lives, although they remained reserved, and would allow me access to photograph these amazingly private and solemn events such as funerals for community members rarely seen by the outside world. It was and remains one of the more special projects I have been able to photograph in my career.

I haven’t been back in several years, but spent the good part of close to five or six years making various trips to the abbey to photograph. Many times, I would only be allowed to photograph for an hour or two at a time. The perseverance paid off and I was slowly able to document their life. I encourage photographers to don’t give up if you are denied access at first as I was. That said, you can’t go into a situation thinking our cameras entitle us access. You have to be patient and let subjects know you are not just there to just take images, but to honestly learn about them and their lives. Our cameras don’t entitle us to anything and in this new digital age I think people are becoming much more concerned with images in general and privacy issues. But if you are respectful, real and can earn a subject’s trust, doors you never imagined would open can and will be opened to you.

What is your photographic philosophy?

When I was just starting out I just wanted to get the picture, get it out on deadline and beat the competition. I cared about subjects, but probably cared more about making a dynamic picture that told the story and then move on to the next thing. I guess that was the philosophy of my news photographer mindset. Over the years though my work and thought process has changed vastly. I now approach subjects with great empathy. I care much more about learning about my subjects for who they are and where they come from in their life than I do about the general pictures I take. This has really allowed me to have a much deeper connection with my subjects and in most instances I feel my pictures are much richer and full and offer a deeper understanding of the person and their environment. For my personal documentary projects it’s much more about how I can leverage my pictures so they can affect change for the specific subject matter I am photographing. I still want them to be journalistically sound, well researched and technically proficient but I’m much more concerned with impacting the viewer in a deeper way and with more meaning than just a skimming glance at the image. I would much rather they say how can I get involved than oh, that’s a nice picture and move on.

This change in attitude is why for the most part I stopped entering photo competitions many years ago. There was a period when I entered all the time and felt that was my validation for who I was as a photojournalist. I guess it basically fueled my own ego. Now I am much more concerned with my subjects and their perspective and if I have done everything I can to fully and truthfully documented their story. I think it’s just a matter of maturing and becoming more confident in your craft. My wife is the great equalizer. She encourages me and my work, always has, but has this amazing ability to bring me back down to Earth when I get too focused on the “me” part of the work. I remember feeling pretty good about myself after having a fairly decent sized spread in a book project and her saying, “Remember, tomorrow you will wake up and still have to put your underwear on one leg at a time just like everyone else.” It was humbling and a great perspective adjustment. I’m thankful for her and my kids who just see me as dad. I think inside all of us we want to be recognized and validated and with them I don’t need my pictures to do that for me anymore. With them, I’m enough.

Tell us where in the world you are. What are your plans for the future?

I live in New England in the state of Connecticut. My town is about half way between New York City and Boston, so we get the benefit of being close to both the countryside and the cultural diversity of the city.

As far as the future is concerned I’m still committed to the Batey story and also building my advertising and commercial client base. Hopefully I can generate some interest in the Batey subject and the plight of the sugar cane workers. The work is important to me and it’s just an issue of time and resources to continue working on it. I have also recently become interested in the new drone and video technology. Much like the iPhone, I’m sure there will be a way to incorporate that technology into my work, but I don’t want it to just be a gimmick. It is still very, very new to me so I haven’t had enough experience with it to be able to judge how I will be able to utilize it in my work. We’ll see what happens with that. I still believe in the power of the still image though. I think a still image can evoke an emotion in a deeper way than video does. I just don’t think you get the same feeling with motion. I have yet to go into a friend’s home and seen an iPad stuck to the wall looping video, but I do see pictures hanging on the wall, so I guess the still image isn’t dead yet.

robertfalcetti.com

photoshelter.com