Dustin Shum was born and currently lives in Hong Kong. He graduated from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University with a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Degree in Photographic Design. A photojournalist for more than ten years, he now works as an independent photographer. In his work, Shum focuses on the relationship between individuals and urban spaces, the living conditions of local disadvantaged groups, and the transformation of Chinese cities and towns in rapidly developing economy.

His works have been exhibited in solo and group shows locally and internationally, and have been collected by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Hong Kong Heritage Museum, and private collectors.

How would you describe your style of photography?

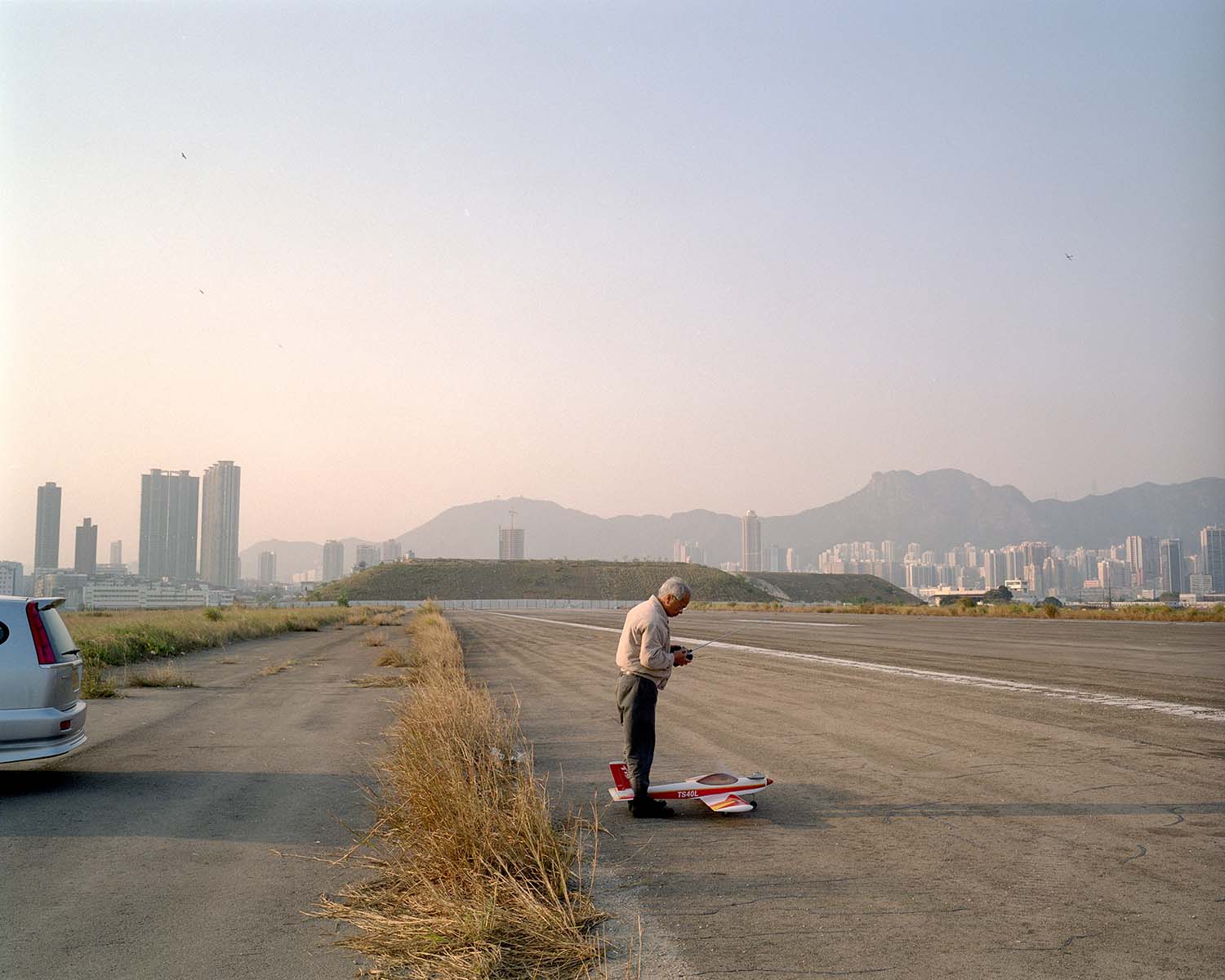

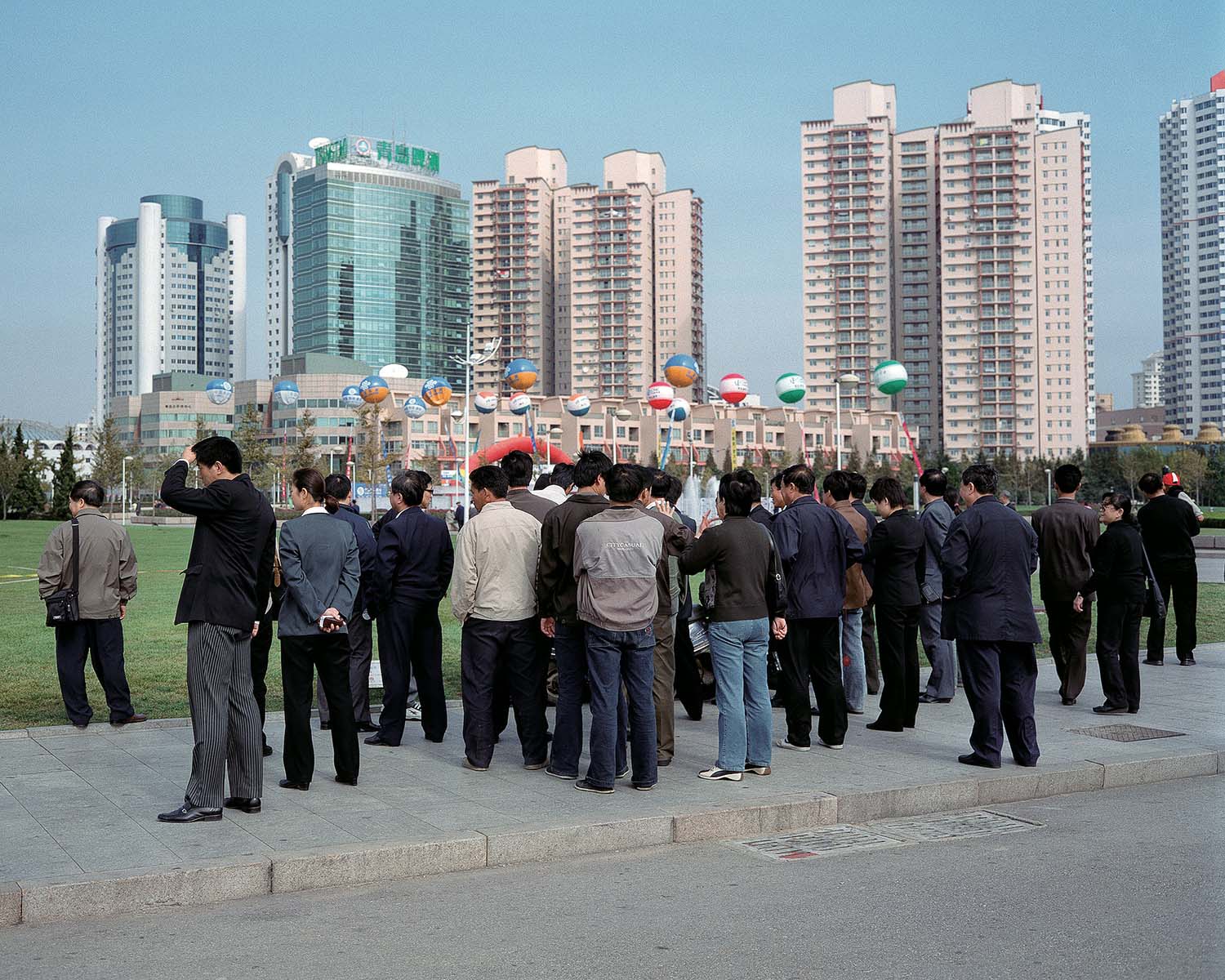

I think my work finds its home in the realm of documentary photography, and I try to tell my stories with a different kind of narrative and visual language. My themes are always about social reality in Hong Kong and China. Instead of expressing my opinion in the classical humanist documentary style, I attempt to articulate it in a more untraditional way, especially through the portrayal of man-made or urban landscapes. These landscapes are often accompanied with a political agenda. I try and ask: what are the consequences of these man-made landscapes?

I am also enchanted with how a deadpan visual style is often paired with the common subject matter. The landmark exhibition “New Topographics” in the 70s cast a huge influence on me but it takes me quite a while to understand how to utilise the concept in my documentary works and put it into the context of my home city. I think all of the above elements create a sense of detachment in my works which I hope helps the viewer to justify the topics without prejudice.

Architecture - or the aesthetics of the built environment - seems to always be present in your projects. Why do you think you are drawn to these themes?

For me architecture (especially infrastructure) is a way to manifest the power of authority. I concern myself with not only the aesthetics of these architectures but how they affect the lives of ordinary people. For example, my projects are often about overlooked architectures such as parks, shopping malls or public housings. These shape our lives, values and cultures. We are in awe of them but at the same time we feel powerless to them. The aim of my projects is always about scrutinising the subtle quality, the good side and the problematic side of a place and a city through its structures. In the end it’s always about the living conditions of humanity.

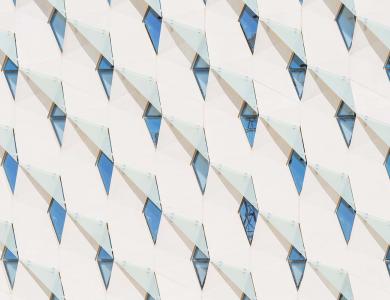

Tell us more about your series ‘BLOCKS’, in which you call the buildings featured: "artificially engineered residences of happiness"

BLOCKS is about the public housing in Hong Kong where nearly one third of the population is living. I have spent most of my life in public housing so I know well that the decors of the building attempt to provide a happier environment for people who feel desperate about living inside. Over the years the government has tried to improve them by refurbishing the hardware and repainting the exteriors of the older housing estates with vibrant colours. But this cannot cover up the dark reality: low-income, unemployment, disabilities, family problems, new immigrants, and the ageing population of the residents. An eerie melancholia permeates these blocks, in sharp contrast with their bright facades. I want to show this absurdity with my images.

You have published numerous books in your career so far. How do you approach the editing process of a publication versus that for online media?

I think online media is a more linear presentation of images while books are more to be viewed as a whole package. When making books I try to loosen myself up and try not to be a control freak. I try to do this because I am constantly looking at my work and maybe my concepts can become too rigid. So I always leave the editing freedom to a third person who may not totally understand my works; this is usually the book designers. Besides keeping me from being bored by my own works, viewing and exploring them with fresh eyes often provides original ideas. I then fine-tune their decisions. Sometimes there can be great input and sometimes there can be disasters. It’s always an adventure and a risk. I think one should try to jump out of your comfort zone and embrace the unexpected sometimes. Book-making for me is more like a passage you should experience rather than aiming to sell a product.

Do you have a photographic philosophy?

I keep questioning if I have a photographic philosophy of my own. I agree with the views of Japanese photographer Takuma Nakahira, who passed away recently. Like him I see photography as a way to counter the sometimes overwhelmingly sentimentalised, poeticised or romanticised vision toward reality. While that’s the bright side of the moon, I would like to deal with the aspects of photography that are like the dark side of the moon. These aspects may not be romantic, poetic, or sentimental at all. And they are always hiding from the public’s consciousness. Photography walks the line between the two.

Can you tell us about a current or future project you have planned?

I’m working on a photography project in China but I don’t want to disclose too much since it is still in a developing stage. You never know if it will turn out to be in vain or not. I also devote my time to contributing articles on photography for local media. Writing is sometimes very tedious for me, but it provides me a chance to encounter issues that I rarely spend time to think about. It’s also helpful to develop my ideas in my projects.

I have other projects which are not purely about my own photography. Two years ago I found an exhibition space in Hong Kong called The Salt Yard. Now the space is closed but I still manage the affiliate online photobook store. It takes up much of my time and doesn’t generate any profit. But it always puzzles me that if I can’t find any audience or readers of my exhibitions or books, it isn’t worth any of my effort to do them. So I think a platform to promote the photobooks culture here is important. I have also started to work with a veteran Hong Kong photographer on his own photobook and I hope it will come out next year.