For This Week's Focus we talk to Xueying Chang about her series Gi Gi. Check out her takeover on our Instagram feed here.

Your practice as a visual artist is extremely diverse, you work in photography, video, and graphic design. How do they feed into one another?

On one level there’s no difference as they’re all tools for creativity and connection. Photography as an art form is constantly evolving, and its interrelation with video, design and other arts practices is blurrier than ever. Using different mediums provides me with more creative possibilities to develop ideas and impart meaning. When working on a multimedia project, I’ll make each medium take on a different role, to serve the greater story. Each medium complements the other and offers the audience multiple ways to access the subject or theme. Sometimes a video piece can help make a conceptual photo series more concrete or sound can add an experiential dimension to still photography. Different arts mediums are like different vantage points, when you change the way you look at the same thing, you come away with a deeper understanding.

Tell us more about your compelling series Gi-Gi. How did you meet Gi-Gi, how long did you photograph her for? Did you have specific shots in mind when creating the project?

In the spring of 2019, I received a group email from my professor asking if any of us would be interested in helping photograph an elderly artist’s artworks as her family wanted to publish a collection of her lifelong achievements. At the time, I was desperate to get over a tough breakup, so I was willing to accept any kinds of work - paid or unpaid - just to fill my free time.

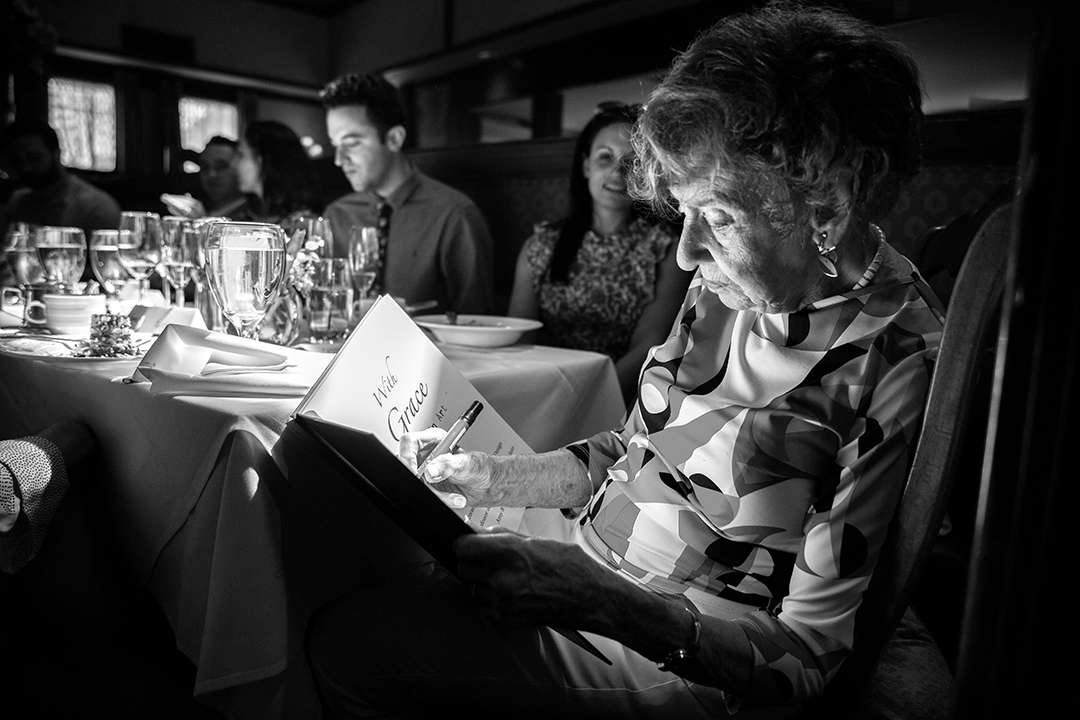

In late March, I met Gi-Gi and her nephew Michael, who had contacted my professor, for the first time at her home in Bethesda, Maryland. She was an outstanding artist who dabbled in painting, collage, sculpture, and other fields. Her name was Grace, but her grandchildren loved calling her Gi-Gi, which was short for Grandma Grace.

Soon after the first meeting and discussion, I set up a temporary photo studio in Grace’s living room. I arranged the backdrop and lighting and then started my work – photographing all the art works made by Grace during her 100-year life. Sometimes she would sit quietly on the side of my studio and watch me shooting. When I was curious about the figures in a painting, she would first meditate for a while and then tell me the rich and moving story behind it. Outside working hours, I would sit down with Grace and her family to have some meals together and talk about their family story and my school life.

Instead of doing research and thinking about the visuals in advance, every shot from Gi-Gi was very spontaneous. I just happened to encounter those moments and capture them. The series never had a formal beginning, and I thought it would never have a formal end either – I would continue to take photos of Grace for as long as I continued to visit her. However, just one month before Grace’s 101st birthday, I learned that she had passed away peacefully at home. At that moment, I realized that the series was really over, and something inside me would be lost forever.

To be honest, for a long time before photographing Gi-Gi, I had been struggling with my new life in the United States and had lots of self-doubt. I didn’t think I was able to tell someone else’s story well then. Photography is not as easy as it looks. Until one day, my photography professor saw this series. She sent me an email asking me to be confident in my abilities as a photographer. When people see the photos many say, “Your photos reminded me of the time I spent as a child with my grandparents” or “I just called my grandparents right after I saw your photos.” Since then, I began to change the way I view my role as a photographer and realise the value of storytelling. As a storyteller, I observe, reflect on, and then process a concept, a symbol or a connection in a visual way to the audience, and at last receive their feedback, which becomes the nourishment for me to tell the next story. The bonds that I develop with my subjects stay with me long after our work together is finished.

Why did you feel B&W was the right fit for this series?

These photos were originally in color in my first edit. Unlike people’s image of the elderly who are always withered and feeble, Grace was an energetic person with a lively mind and a sharp tongue. My friend called her “a pistol,” constantly questioning, commenting, and joking, including a smidge of good-humored sarcasm. I had no doubt that this series should be in color, to reflect Grace’s true personality.

However, one day after shooting, we were having tea and chatting as usual, when Grace suddenly said matter-of-factly that she had fallen down the night before and it had been a long time before someone noticed. Then she grabbed a handful of popcorn that her helper just served and ate it slowly, as if she hadn’t said anything out of the ordinary. Grace’s house was surrounded by lush forest and the sun filtered through the trees and her window, casting a warm orange glow on her face. At that moment, even though the scene was still colorful, however, I started to feel everything in front me as monochromatic. Longevity can be a blessing, but also a curse. I realised that Grace was also burdened with the pains and fragility that came with aging despite her strength and zest for life. Black & white conveys a delicate balance of tenderness and isolation, which make the series quiet and beautiful but also vulnerable and heavy.

Elderly people are recurring subjects in your portfolio. How did you develop this interest?

Most of my projects originate from personal experiences. I was raised by my grandparents in a senior community where all my childhood memories took place. There were hundreds of old residents who had worked in a textile factory for a lifetime, and after losing the ability to continue engaging in labor work, they applied for retirement and then devoted the majority of their time raising their grandchildren. After entering elementary school, I moved to live with my parents for a few years, but then moved back to my grandparents’ place again. We continued living under one roof until I went to college. I would say this experience shaped a very essential part of who I am.

I always consider that aging and death are two themes that constantly connect us. Unlike many others who don’t often openly talk about this due to their anxiety or fear, I found myself fascinated into the topics. Through my personal experience living around the elderly, I witnessed how desperate they were in search of listeners. They had their own stories to tell and didn’t want to live in the stereotypical representation given by our society anymore. Both their strength and vulnerability touched me and made me realize that I should become the person to help express their emotions and reveal how their lives are related to ours.

Portraits are central to your photographic practice, has there been a particularly memorable encounter?

Portraiture always remains a ubiquitous force in the photography world and it is way more complicated and meaningful than many people consider. It was through taking portraits of my family and friends that I first started to practice and explore photography, and until today, I still regard it as a captivating approach to help beginners understand the mission of images. After I took up documentary photography, again, I found portraits could always construct a great part of meaning for the whole story. Through the process of making portraits, I could also see deeply into my subjects and their subtle and personal emotions.

Last year I was covering the story of the go-go music community and their #dontmutedc uprising in the Shaw area, Washington, D.C for the Smithsonian Institution. Go-go is the quintessential icon of DC’s “Chocolate City” era, and the local African Americans have been fighting for the existence of their music and cultures and standing up to the gentrification and racial inequality for decades. There was always music and singing on the streets, and I was very impressed to find so many people rooted their lives in the music and let it become part of their personalities. Sometimes I even put down my camera and paused my work to dance to the music with them together.

You’re currently undertaking a photography degree at university, what do you think this academic environment has brought your photography? Is there anything particularly useful you’ve learned during your studies?

Studying photography in an art school made me realize there are many people who have faith in the power of images and are eager to share their vision with the world. Being lucky enough to work around some of them undoubtedly strengthened my belief in what I am doing. Before, I had never called myself “photographer.” I did love capturing everything I saw with a camera but never thought about whether there was something that I truly cared about and wanted to express.

During the past two years, the academic environment both helped me hone my technical abilities and discover my mission as a photographer. I developed the skills I need to freely express myself through the photographic medium and also became more self-reliant and independent. I remember in one of my classes, we discussed the photo book called “Undocumented” by John Moore about the issue of undocumented immigrations to the United States, which had a big influence on me. Then I realized that how important it is to have storytellers in the world and I couldn’t just take photos randomly without any purpose anymore. Photography can be a tool or even a weapon that protects the groups whose experiences are often ignored or supports the people who mean something to me.

What’s next for you and your practice?

Currently, I am working on my ongoing thesis project “My Darling, Stay Gold”. Unlike “Gi-Gi”, “My Darling, Stay Gold” is a long-term multimedia project that explores a deeper and more complicated theme: how the older generation is breaking people’s stereotypes and building up a “senior utopia” for themselves through the village movement in the United States.

Although the pandemic did shut down the world and interrupt my plans, I’m glad that there is still something that I can prepare in advance for my next steps, such as writing my documentary production plan or playing around designs for my future photo book. I also keep in touch with my subjects who have been trying to stay connected and maintain normal social lives since the pandemic. They adjusted some of the group activities to a virtual way such as having meditation and book club meetings via Zoom. Frankly speaking, it is unexpectedly intriguing to observe how they handle their post-pandemic lives, and I plan to document this remotely.

As far as my personal career path, I just completed my position with the Smithsonian Institution and will join the National Public Radio (NPR) this month, which is one the most esteemed news organizations in the United States. That will be a new journey for me with plenty of unpredictability and surprise where I can continue to explore the mission and vision of storytelling and also further understand my role as a photographer and a multimedia journalist.