DON'T MISS OUT

The Sony World Photography Awards exhibition is back with a powerful mix of photography and stories from around the world, featuring top talent and fresh perspectives.

Somerset House London, 17 April - 5 May.

The Sony World Photography Awards exhibition is back with a powerful mix of photography and stories from around the world, featuring top talent and fresh perspectives.

Somerset House London, 17 April - 5 May.

Blink is a platform connecting thousands of media freelancers with publishers, brands and agencies who need high-quality content produced on location anywhere in the world.

---

Open Society Foundations (OSF) has had a long history of supporting documentary photography, particularly work that covers issues on human rights and social justice. This year, they are holding the 23rd iteration of the 'Moving Walls' exhibition. The included projects are both journalistic and conceptual in nature with an aim to portray people as agents of change, rather than victims. Here, Amy Yenkin the Director of the Documentary Photography Project, and Siobhan Riordan, the exhibition associate, talks to Blink’s Laurence Cornet about the 'Moving Walls'.

Laurence: Can you talk about why Open Society Foundations is driven to support photojournalism?

Amy: To understand why the foundation supports photography you have to pull back a little bit and see the funding of photography in a broader context. We are a political foundation and advocacy oriented. OSF has been supporting independent voices documenting social justice and human rights issues through journalism, film, and photography. So, it’s not about supporting photography for photography’s sake, but for what it can do in the world to advance social issues.

We started funding photography because many photographers were doing long-term independent work on human rights and social justice issues, but support for these projects was diminishing as the media environment changed.

Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas conceived of the exhibition 'Moving Walls' in 1998 when OSF moved into an office space on West 59th Street. Seeing the vast number of empty walls, Susan thought that a photo exhibition would be a good way to display the issues the foundation cared about while also supporting the photo community.

Laurence: Apart from Moving Walls, how does the program support photography?

Amy: We have funded organizations that support photography such as the Aftermath Project, Art Works Projects, and the Magnum Foundation, as well as Market Photo Workshop, a school that trains photographers in South Africa. We have, in the past, funded individual photographers from Central Asia and Caucasus who were working on human rights stories in their home countries. We paired them with a mentor who worked with them for six months. For 10 years, we have awarded a grant called the Audience Engagement Grant, which supports photographers who partner with NGOs to bring their work in front of audiences that are in position to effect change.

In addition to those efforts, we started an Instagram account over a year and a half ago, and every week a different photographer takes over the feed.

The foundation’s photo editor, Maggie Soladay, has reached out globally to find photographers documenting diverse stories and we now have over 86 thousand followers. For people who are interested in human rights and social justice photography, it is a great place to see fresh work on important topics.

Laurence: Has the site been used for other purposes besides a gallery space?

Siobhan: It’s interesting that we call it a gallery space because at the same time it’s not. It has a space dedicated to exhibitions that draws an audience interested in photography, but it is also a functional space where people like civil society actors, academics, researchers, activists and staff come in for meetings and conferences centered around the issues that the foundation is dedicated to. So we’re able to bring a diverse audience together in a way that few other spaces can.

Amy: With this new space we really see different opportunities. Moving Walls brings together this community of artists as well as advocates, NGOs and policy makers, and it is always interesting when they come together in the room to discuss an issue.

Laurence: How about this year’s exhibition?

Siobhan: When our selection committee got together to review the applications we had received for the current show, Moving Walls 23, we saw these five bodies of work rise up together, all touching on the idea of a journey. Both literally, in terms of a migration, but also in a more abstract sense, in terms of a creative journey or a journey of identity.

Amy: One of the other things that attracted us in these works was that in all the cases, they were showing the perspective of empowerment and self-determination.

Laurence: Can you talk about the variety of work you’ve selected and what the collection says about documentary photography today?

Amy: We’re really excited about Liam Maloney’s work and the way it pushes the boundaries of documentary photography. There are a lot of debates about what is photojournalism, what is documentary, and what is fine art. While it’s important in news reporting to adhere to a journalistic standard, Maloney’s work challenges its rigidity by taking a more conceptual approach.

Shahria Sharmin does this too; we love that her depictions of trans-experience contrast the conventional narrative. Rather than perpetuating stereotypical imagery that emphasizes story of passive victimhood, Shahria conveys a less common and more intimate perspective of their personal hopes and dreams as they seek acceptance through each other, at home, or in their adopted country.

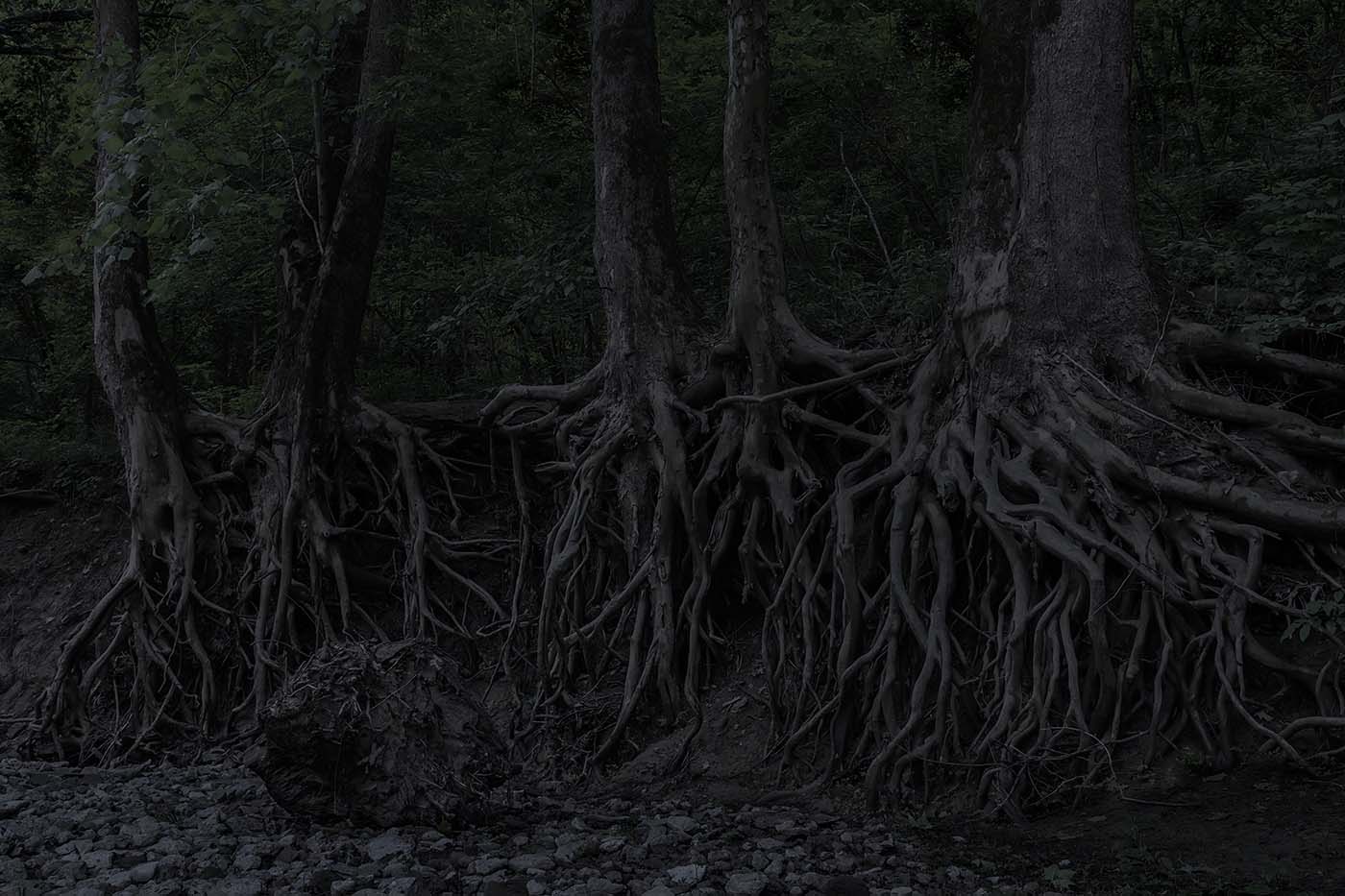

And then there’s Jeanine Michna-Bales’s project that documents the journey that many African American men, women, and children took in the nineteenth century to resist slavery and escape the South using the Underground Railroad, heading north to Canada. The artist relied on research and oral history to imagine one path toward freedom and re-envision various sites and stops along the way.

Laurence: How was the exhibit designed to highlight the photographer’s message?

Siobhan: For instance, Liam Maloney’s Texting Syria is an immersive installation that shows back-lit portraits of Syrian refugees living in a slaughterhouse in Lebanon after having escaped the conflict in Homs. These are portraits of them at night, texting their family and friends who are still trapped in Homs. But alongside the portraits, Liam presents the actual text messages, translated into English. These text messages are included into the exhibition in two ways: a selection of them are shown on a monitor, so that you can read them side by side to the portraits, and there is also a phone number you can dial to start receiving those messages on your phone. To interact with the work on a level that intimate, to have your own phone ring or buzz with a life or death message, is a powerful emotional experience.

That’s something we tried to do for all the artists’ installations, to include some additional pieces of the story. For Glenna Gordon’s work about northern Nigerian romance novelists, we were able to feature their books in the exhibition. We created an installation that puts you in the market place where these books are sold, and we included translations of some of the books as well, so that you can dive into those stories first hand.

Laurence: Does the exhibit specifically aim to break the boundaries of photography and documentation?

Amy: We hope that the 'Moving Walls' exhibition encourages the field to rethink traditional boundaries of documentary photography. Sometimes that involves bringing the subject’s voice into the work; sometimes it means taking a more conceptual approach. We want to show photography that portrays people as agents of their own change, as opposed to victims of their situations. We feel it is a very important shift that needs to take place in photography, not only stylistically but also in the way photographers report about people.

Interview by Laurence Cornet / laurencecornet@gmail.com

Edited by Sahiba Chawdhary / sahiba@blink.la

The Sony World Photography Awards exhibition is back with a powerful mix of photography and stories from around the world, featuring top talent and fresh perspectives.

Somerset House London, 17 April - 5 May.