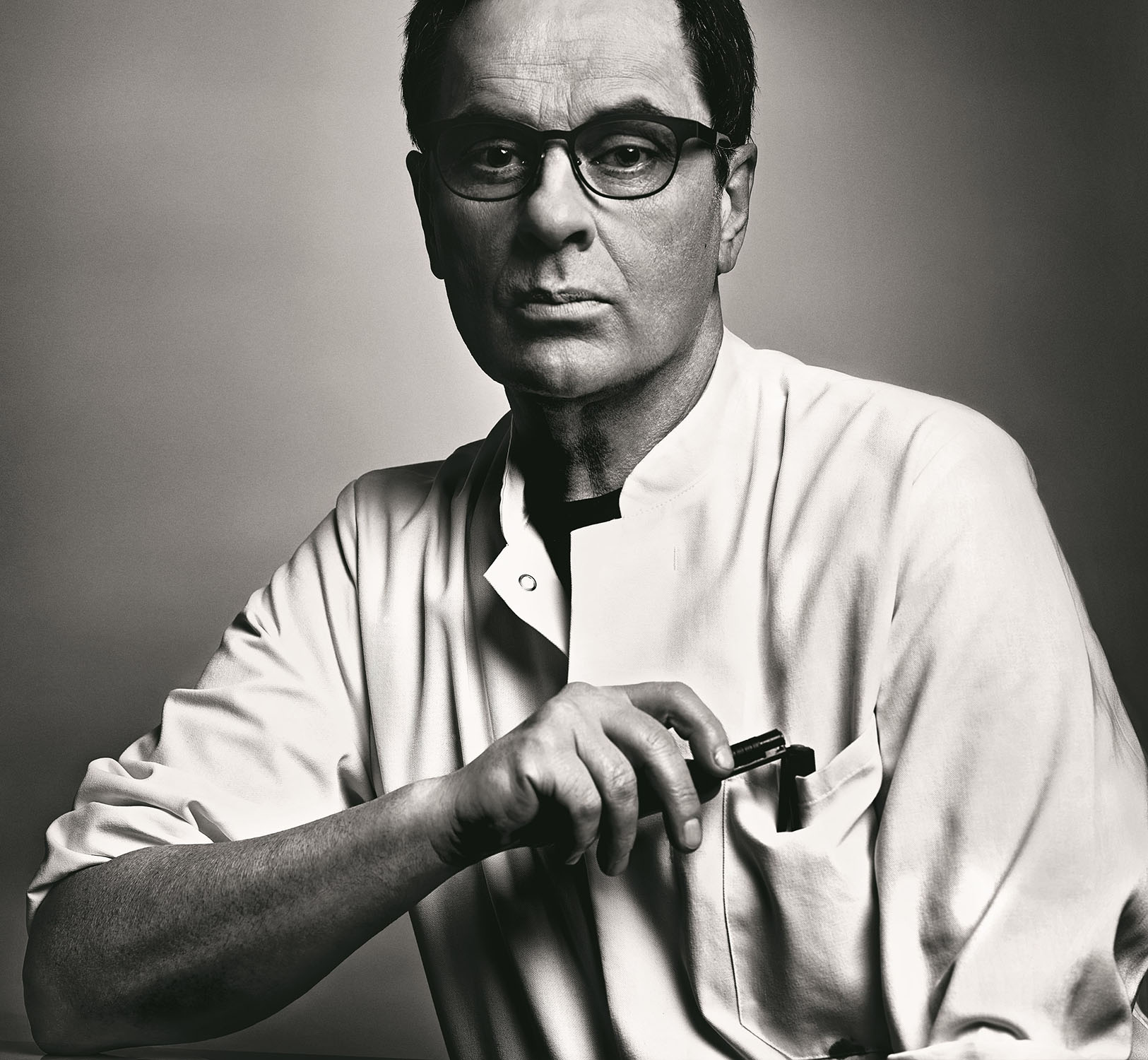

To celebrate this year's Outstanding Contribution to Photography recipient Gerhard Steidl, we're asking you to submit any question you might have about creating photobooks. The best questions will be answered by Steidl for our special Steidl Day video, released on 25th June. To kick things off Digital Content Editor Anna Bonita Evans asked Steidl a few questions of her own...

You have 48 hours to send us your questions. Deadline 18 June 11am (BST)

Do you remember what you felt when you held your first printed photobook? What are your thoughts thinking back to that project now?

One of the first photobooks I both printed and published was Karl Lagerfeld’s Off the Record from 1994, also the first book I made of Karl’s photos. I remember the challenge of it – all the test-prints on different papers and inks to find exactly the right recipe. Today I’m still very proud of it and I don’t think it’s aged at all.

In How to Make a Book you sit down with Robert Adams and his wife and talk about your father, who worked in publishing production. Were there other members of your family who provided you with creative influences?

My father worked at the local newspaper the Göttinger Tageblatt where he cleaned the printing presses. His job wasn’t creative as such, but it was definitely my beginning in the world of printing: how to use paper and ink to make something that transcends the raw materials. My bookmaking influences are often from history, like Johannes Gutenberg, who took care of the conception of his books, their typography, illustrations, printing, binding, and even sales by himself. Everything was under one roof – just like at Steidl.

When did you decide to dedicate your life to creating photobooks?

I’m not only dedicated to photobooks, but to books in general – Steidl makes German literature and non-fiction titles as well. It’s definitely been an unexpected but organic journey since opening my first screen-printing workshop in 1968: somehow one thing leads to another.

What is your most ambitious book to date?

The one I haven’t made yet.

Since you started your career in 1968, you’ve produce a mammoth amount of books each year, around 300 titles. Which title has given you the greatest pleasure?

Impossible to say – that’s like asking a father who’s his favourite child! There are different challenges and pleasures depending on the particular book I’m making – whether it’s creating an intricate facsimile of a seminal title like Henri Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment, making the definitive edition of Robert Frank’s The Americans with him, or printing a young photographer’s very first book.

It appears in How to Make a Book you had a real affinity with Robert Frank; there is a beautiful scene when his wife June paints your portrait while Frank documents the process. Can you tell us a little bit about your friendship?

I began working with Robert Frank in 1989 when the Swiss publisher Walter Keller asked me to reprint The Lines of My Hand for his imprint Scalo. Walter thought Robert and I would get on well on press and he was right – since then we made more than 30 books together. I learnt so much from Robert as a bookmaker; he always wanted a simple book, a humble book, never anything overbearing or overblown. Even in his 80s and 90s he was still exploring new forms for his photobooks, like the series of visual diaries we made together, from Tal Uf Tal Ab in 2010 to Leon of Juda in 2017, which combine iconic photos with more personal Polaroids and text fragments in softcovers like private albums or scrapbooks.

Considering the changes that the printed book has had over the past 10 years or so, how might we consider it as a medium in its current form, and what changes do you envisage for the photobook over the next 10 years?

I wouldn’t say I make photobooks any differently to 10 years ago – the goal of creating a book that best expresses the photographer’s vision hasn’t changed. Photobooks have already proven their worth in the age of digitalization: all the visual and haptic qualities of a well-made printed book, from the tint of the paper, the smell of the inks, and the touch of an embossed cloth cover, simply can’t be replicated in digital form. I think the debate of analogue versus digital is also somewhat over. The issue is now more analogue and digital: how do they interact and benefit each other, how can we use the best of both worlds.

There’s an interesting story in How to Make a Book with the photographer Joel Sternfeld; he wants to simulate the look of iPhone images in a fine art printed photobook. This documentary was made (almost) 10 years ago. How do you think technology has dictated your recent clients’ creative thinking towards making photobooks?

At Steidl we always have the most up-date versions of computer and printing hardware, whether it be Photoshop or our plate-making machine – I have no nostalgia for technology. Technology should not dictate creativity but facilitate its expression.

Dayanita Singh’s Museum Bhavan, Gordon Parks’ Collected Works and Andy Warhol’s Red Books are among your publishing triumphs. Can you expand on this idea of ‘The Book as Multiple’?

I see the photobook as a multiple in the tradition of the artist’s multiple – a series of identical objects made or commissioned by an artist. Producing such multiples for artists like Klaus Staeck and Joseph Beuys was an important part of my education and training. I follow the same approach when making a book: it’s a limited print-run of objects that embody the artist’s vision and make it accessible to a wider public. (That said, the photobooks we make are of course not artworks, and should not be viewed in such a precious and untouchable way.)

Buying a complete set of Robert Frank’s prints from The Americans is today nearly impossible (even if you had the money), but anyone can go and by the book, knowing that the photographer oversaw and approved it as a multiple of his work. Joakim Eskildsen put it well once: “People often ask me if they can buy one of my prints but they tend to back off once I tell them the price. So I say, ‘Just buy the book! It’s got hundreds of pictures! Buy two books, so you can cut up one and frame the photos!’”

How important is it in the publishing industry to build a brand?

Branding and marketing is not something I consciously think of; my focus is always just on making the book at hand as good as it can be. That said, we make sure that “Printed in Germany by Steidl” is stated in each of our books. It’s important that the reader knows that each and every Steidl book was printed on our Roland 700 press at Düstere Strasse 4 in Göttingen. There’s only one source of production for our books.

For you and your team at Steidlville, what dictates the book production process: are decisions made from the heart or the head?

Intuition is incredibly important, and mostly the first decision is the right one. But at the same time our focus is on trade books that are affordable and accessible. So for example we’re careful to keep large books nevertheless under a certain size so they can be bound mechanically and binding costs, which would inevitably be passed onto the buyer of the book, don’t explode.

You select which books to publish by whether you think you’ll learn something from the photographer: you are a ‘master student and the photographer is the professor.’ How many images do you need to look at before you know whether or not you’ll learn something from that photographer?

Sometimes just one, sometimes a few in a series; it depends on the project.

How do you make words and images harmonize most successfully in the books you create?

That depends on the book; layout and typography, and the relationship between word and image are always individualized. In terms of choosing the text itself, sometimes a photobook just has a single quote, something lyrical and suggestive that ties everything together, like in Dayanita Singh’s Sent a Letter: “Sent a letter to my friend, on the way he dropped it. Someone came and picked it up and put it in his pocket.” Sometimes over the years a text becomes integral to a photobook’s message and reception, like Jack Kerouac’s in Robert Frank’s The Americans. Or a text can be crucial in contextualising a book and placing it within an artist’s personal history, like Nan Goldin’s new introduction in the revised edition of The Other Side.

Aside from photography, what other creative mediums interest you?

Fiction is a great passion of mine and shapes our German literature list Steidl – including the work of two Nobel Laureates, Günter Grass and Halldór Laxness, and other authors including Sebastian Barry, Claire Keegan, Colin Barrett, Maeve Brennan, Véronique Bizot and Alexander Pechmann.

After watching How to Make a Book, I’m fascinated to know why on flights you have five iPod Nanos all lined up on table?!

Back then I had a different iPod for each genre of music – jazz, rock, soul, and so on. All those iPods are of course all junk now as the batteries are dead. Which of course is not the case with a photobook! Look after a well-made book and it will last for centuries.

Submit you question now! You have until this Thursday, 18 June, 11am (BST)