Our War is a collection of portraits of people involved in the Libyan Civil War. Why did you steer away from creating the photographs in one distinct style?

This project is not only a collection of portraits of people directly or indirectly connected to the Libyan conflict, but also others enacting their stories. There are two aspects to this work, which collide, overlap and blur: there's the reality of the situation, on the ground, and also how I imagined this reality to be in the 10 years prior to travelling to Libya and since I was informed of Anton’s death.

From the outset, I set out to produce a project rooted not only in Anton’s story (the places he visited and travelled through and the people we met along the way), but also in the very simple premise: how does one tell a story when there is no witness, no testimony, no evidence, no subject?

In the absence of all of these things (evidence, testimony, witness, subject), an imagined reality of the conflict, people, and the circumstances of Anton’s demise, was all I had to make sense of the situation for nearly a decade. I wanted these two dimensions to merge in my work.

Secondly, this approach was also motivated by a very specific concern I have always had about photography and documentary photography, photojournalism in particular: its proclivity to inadvertently misrepresent or outright exploit its subjects. When the power dynamics between photographer and subject are not kept in check, this often leads to photographers producing images that, in my view, only serve to confirm the already held opinions within the dominant ideology about the particular subject they are working on. So in the case of war, how often do we see these tropes: the rebel as the good guy, the freedom fighter as the ideologue, the militias as the bad guys, and war reduced to a simple polarity between aggressors and victims? Reality is always much more nuanced than this. Most people involved in the conflict aren’t ideological. For some it’s a paycheck, for others, it’s a means of survival.

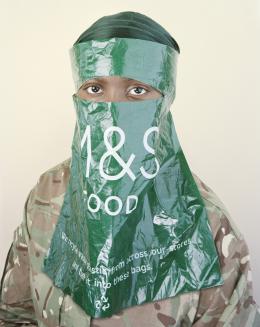

So in order to distance the viewer from the way in which they're used to consuming these types of stereotypes, I photographed people who were not only affected or involved in the conflict but also people enacting their stories. They ranged from descendants of people that fought in the conflict but hadn't experienced the horrors of war directly, and wanted to understand the trauma of their parents or locals. We needed their support for access or information and we’d invite them to participate in photoshoots so we could share our stories with them and learn about theirs. I also selected many of my subjects based on how they reminded me of Anton at different stages of our friendship. Many of these sessions were cathartic and reconciliatory. And this made me realise that photographs don’t have to be the end goal but a means to an end. A means to bring people together and share their stories.

By employing this approach the viewer is never really sure who it is that he/she is looking at (though there are clues here and there). And this not only disrupts the voyeurism usually inherent in the consumption of this kind of imagery but also protects the identity of those I was collaborating with. There is a certain indignity in speaking for others. I’m much more interested in creating conditions in which people that may not have a voice or have found a voice can speak for themselves.

Lastly, as to the issue of aesthetics, I wanted the project to be fairly fragmented and idiosyncratic in its approach. I did not want it to be defined, contextualised, or pinned down by a specific genre or set of aesthetics. Aesthetics, in photography, are a little bit like a Trojan horse. We accept it as a free gift but when we do it colonises us.