Beyond the Frame: Niloofar Mahmoudian

A trip to her university library led Iranian fine art photographer Niloofar Mahmoudian to an intriguing discovery. Contemplating how her findings could feed into her creative output, Niloofar soon produced her powerful photo project. She shares her thinking and meaning behind Retrieval.

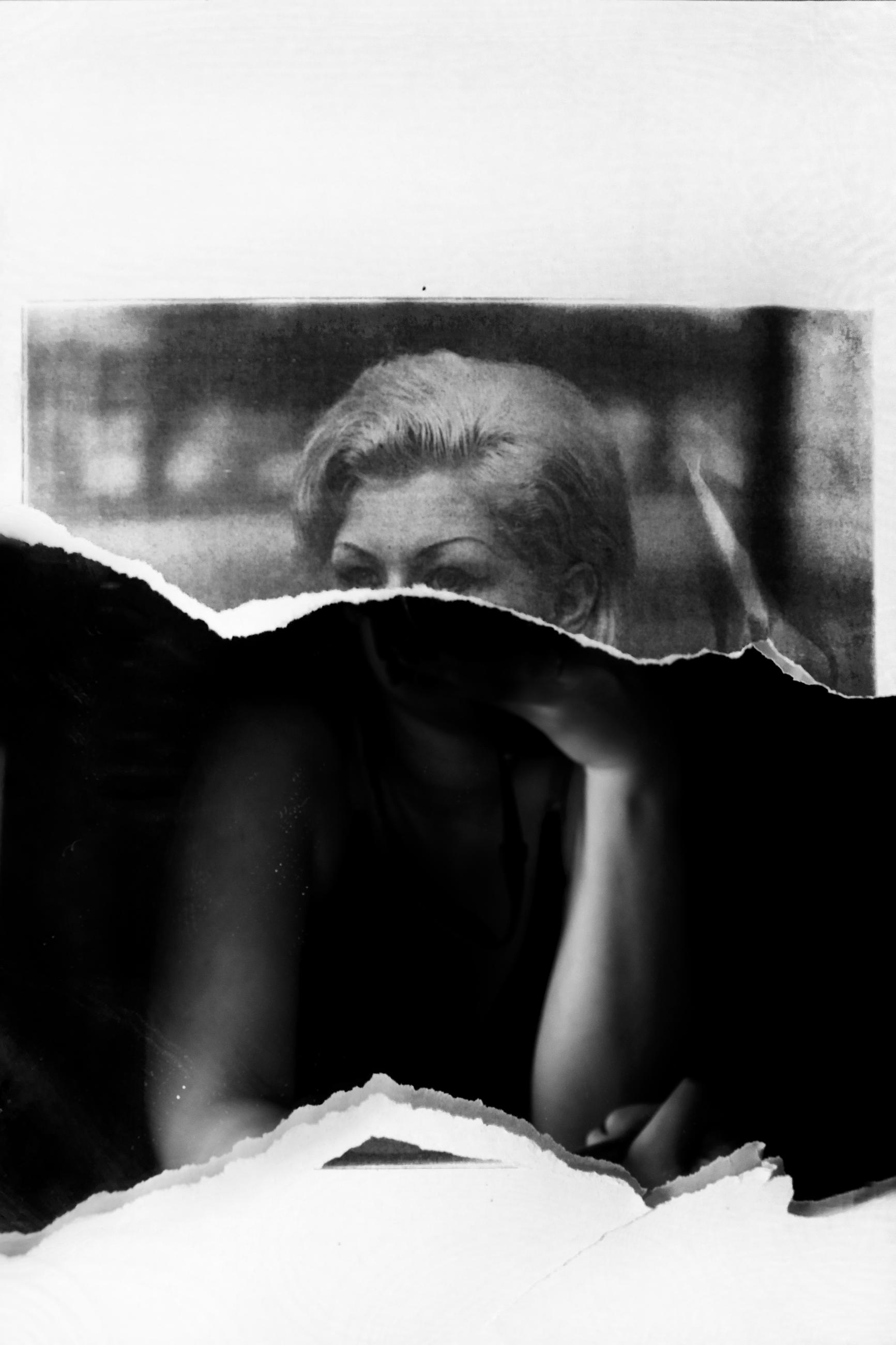

Some pictures had been partially damaged while others were unrecognisable.

I studied photography at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran and, as a student, I spent some time in the university’s library to look through photobooks and study the history and techniques of photography. I started to notice some books had photographs that had been defaced, manipulated or written on with a marker, biro or tape. Some pictures had been partially damaged while others were unrecognisable.

A few books had hateful notes from readers who were angry at the authors or the university because of the content of the photographs – many depicted naked female models. Others were angry at those who were criticising the contentious images, making the pages a place for conflict and debate. For me, those corrupted images made studying and understanding the pictures much harder than they should be. It was one single subject, a woman’s bare body, that goaded those harsh comments. The detractors felt everything but the head should not be seen. The photo was considered sinful and unethical.

These kinds of beliefs drove the Islamic Revolution of Iran in 1979 and many of us adhere to this thinking even if we don't entirely believe it. Looking at every photography book in the library, I found this type of censorship was more evident in books that had been registered between 1979 to 2009. Those years were when people were more radical about these issues. I wanted to respond to this discovery, so I picked every book with defaced images, made a copy of the damaged pages and made some slight changes myself. I tore away at the part of the image that had been censored, put the rest of the page on a mirror and then took a self-portrait showing the parts of the body that had been omitted.

The images came together as a photo series I call Retrieval. All 35 black & white images are presented in a photobook. Each photograph is from a separate book, showing a different part of the body. This picture is from the book Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph. At the end of my book, Retrieval, you can see my complete self-portrait representing the fact that it’s not wrong, sinful, or weird to look at a woman’s body.