Latin America Professional Award: first look

Congratulations to Peruvian photographer, Florence Goupil who won 1st Place for Whisper of the Maize, a project documenting the Indigenous Quechua, Wari, Nahua, Otomi and Wanka communities' perseverance in protecting over 119 varieties of corn across Peru and Mexico.

Winner | The Whisper of Maize by Florence Goupil (Peru)

‘We plant the seeds with the power of the song,’ shares Magdalena, an elder from the Andes. These indigenous communities unveil unique and innovative solutions in response to climate change and the devastating impact of severe droughts. Their tender gestures, songs and poems become a conduit for communicating with nature and healing the Earth."

Janeth Vargas, an Indigenous Otomi woman, sitting on her recent harvest of black or purple corn. According to the National Water Commission, a drought has affected over 65 per cent of Mexico since 2022, severely impacting corn crops. Janeth mentioned that their current harvest is only half of what it used to be. In Ixtenco, the growth of corn is related to the Malinche Volcano, which is represented by a woman with long folded skirts. Ixtenco, Tlaxcala, Mexico.

After a severe drought in the Huancavelica region of Peru, Indigenous Quechua singers Magdalena Gamboa, Vilma Espinal and Gloria Espinal performed the ancient Jarawi songs during corn planting to call for rain and heal the land. According to Quechua cosmology, the Jarawi, a pre-Columbian chant from the central Andes of Peru, is dedicated to the sowing and harvesting of corn and helps the seed grow strong. Huaylacucho, Huancavelica, Peru.

A group of Quechua Indigenous farmers of the central Andes sowing the dry soil using the ‘taki llacta’ technique, which consists of opening the soil with the help of two bulls, before planting the corn seeds. In this town they also maintain the tradition of the ‘minka,’ which involves all of the community members helping to work the land. In 2022, they planted belatedly due to the drought. Huaylacucho, Huancavelica, Peru.

Ulises Hernandez’s hand with teocintle (Zea perennis), the smallest corn cob in existence. Teocintle is considered to be the first wild corn, which was later domesticated into what we know today as maize. The word teocintle comes from the Nahuatl word teocentli or teoxintli, which means ‘God’s corn.’ Ulises grows teocintle on his farm, although it cannot be consumed or sold – he does it for preservation. Ixtenco, Tlaxcala, Mexico.

Lorenzo Martin de La Cruz is a Nahua Indigenous priest and protector of native seeds, seen here guarding his deities’ altar. Lorenzo’s deep understanding of nature and spirituality has made him a vital figure in his community, where he performs rain-calling ceremonies rooted in Nahua traditions. According to Lorenzo, his connection to the god of rain, Tlaloc, allows him to channel the power of the rain through sacred rituals, invoking it to restore balance to the land. Tetzacual, Veracruz, Mexico.

A portrait of a corn dressed as a child during an Indigenous Nahua ritual called ‘Elotlamanistli,’ in the Huasteca region of Veracruz. According to the local Nahua priest, Lorenzo Martin de la Cruz, the corn’s clothing represents their personality and the light of the candle their spirit. The ritual is performed to start a dialogue with the maize cobs, the children of the Earth. Zontecomatlán, Veracruz, Mexico.

A group of Quechua farmers in the Andean region celebrate the planting of corn with a duelling ritual between men and women called ‘Since,’ which consists of throwing corn flour over each other's heads. According to Quechua cosmology, the more maize flour that is distributed among all the farmers, the better the harvest will be. Huaylacucho, Huancavelica, Peru.

Victor Vargas, a Wari medicine man, performs a healing ritual using maize flour and rose petals that he rubs on his patient, Daniel. This will help Daniel overcome his physical weakness and depression, so he can return to work in his fields. According to Wari cosmology, sudden weather changes and damaged agricultural cycles can make people physically and mentally ill. Community of Llupa, Huaraz, Peru.

2nd Place | Alquimia Textil by Nicolás Garrido Huguet (Peru)

Harvesting qolle 4,500 metres above sea level. Without their prior knowledge, the two analogue cameras the photographer had borrowed to photograph this dyeing route had light leaks, which serendipitously aligned with the artisanal quality of natural dyes.

A Van Dyke brown print showing hands picking ch´illka leaves. Before applying the Van Dyke process, the Hahnemühle bamboo paper was dyed in ch´illka. This technique introduced spontaneous effects, giving nature an active role in shaping the photographic image.

Dionisia, Nilda, and Braulia washing the recently dyed fibres in the lake. A unique aspect of natural dyes is their harmony with the ecosystem; chemical dyes would release toxic substances into the lake, but natural dyes integrate seamlessly with the environment, preserving its balance.

A portrait of Nilda, one of the seven Pumaqwasin textile artisans, printed as a Van Dyke brown print on Ilford photographic paper dyed in cochineal.

Portrait of Ruth, one of the seven Pumaqwasin artisans. Just as natural dyeing has unpredictable outcomes, shaped by harvest quality or firewood temperature, so analogue photography never guarantees uniform results. Both processes embrace the beauty of variation, capturing the nuances of organic, imperfect artistry.

Portrait of Braulia Puma, dressed in traditional Andean clothing, among ch’illka bushes. Braulia founded and leads Pumaqwasin, a cooperative of seven women who preserve traditional textile processes, recovering knowledge lost over generations. Focused on sustainability, they minimise their environmental impact and practice equality, sharing responsibilities fairly or sending representatives to ensure tasks are completed collectively.

Harvesting qolle with Liz and her son, Jacob. Due to shifting weather patterns, the community postponed the harvest by a month, as the flowers took longer to bloom.

3rd Place | Yvy-Mara Ey (Land Without Evil) by Mauricio Holc (Argentina)

Ñanderu is the creator of the Mbyá people, who presents himself in a vegetal form (like a tree). His resources are used in a respectful and sustainable manner by the Mbyá people, because in their culture, both the creator and nature are the same – everything in it is a living manifestation of Ñanderu.

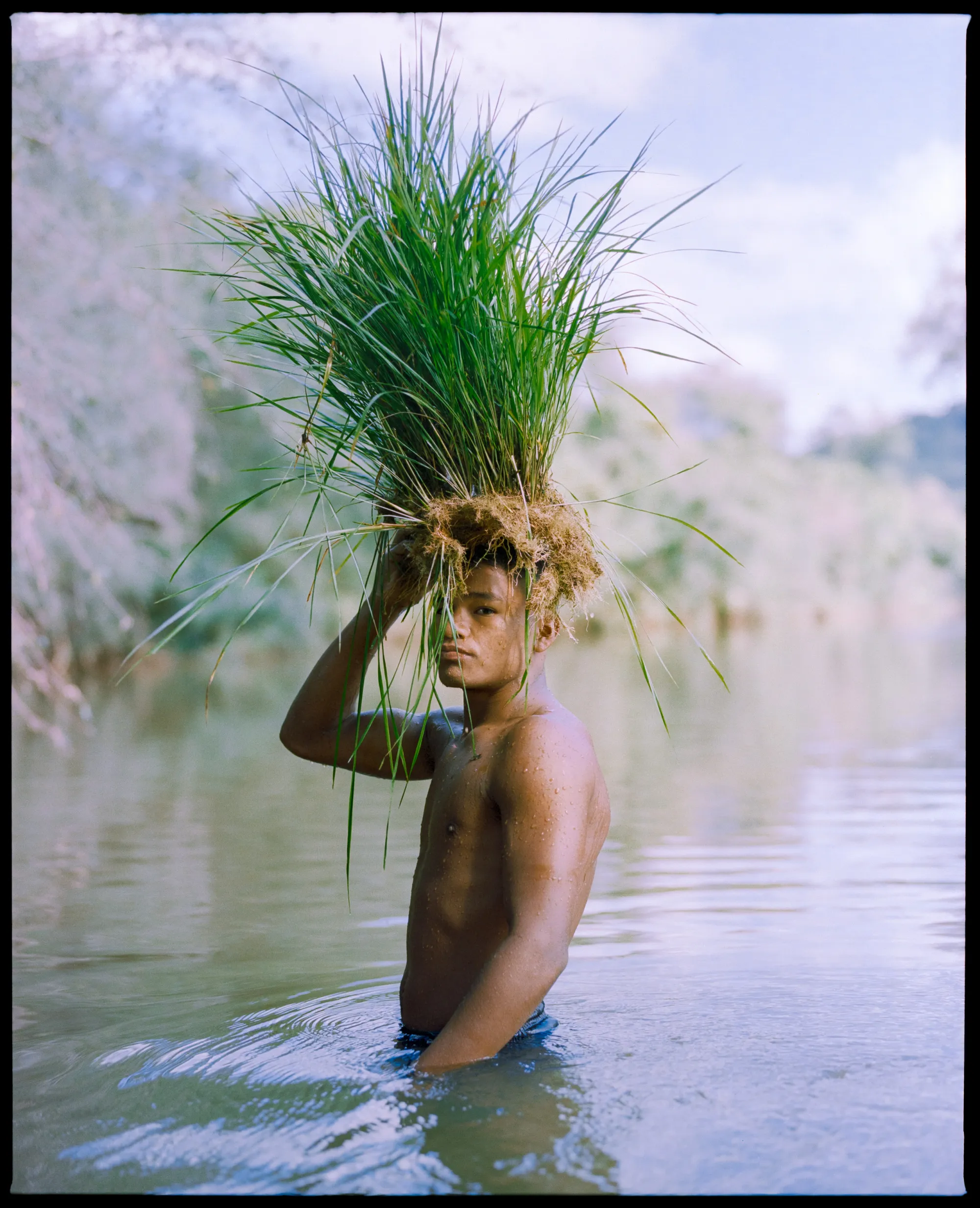

Children are the majority in the Mbyá communities. Their young relationship with the forest and nature is one of leisure and learning, of food sustenance and respect. Water and jungle are fundamental in their life.

A family portrait of the political leader of the Tekoa El Chapá community with his two daughters and his wife.

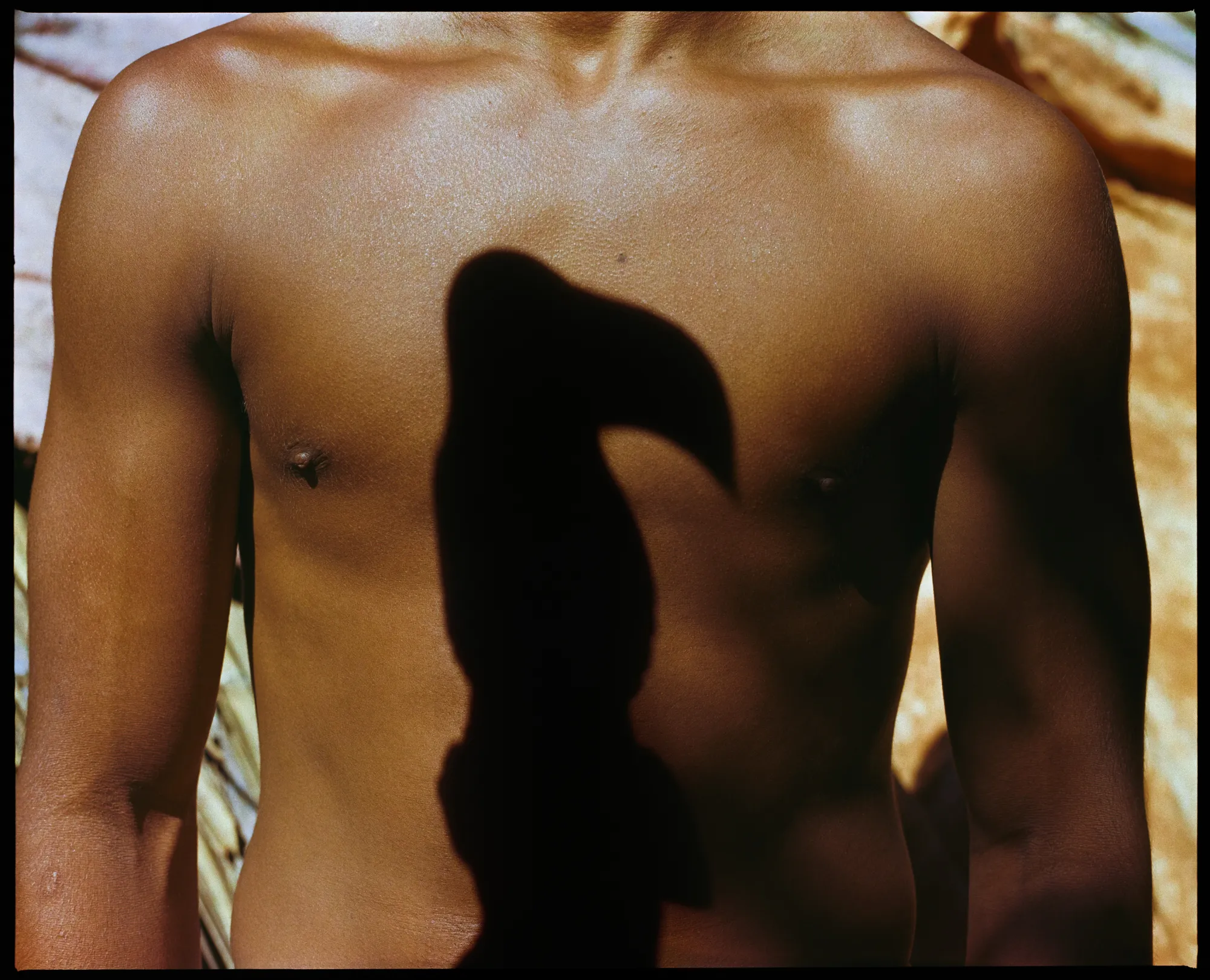

Nature is an intrinsic part of the Mbyá. It not only represents their life itself, but their relationship with it is also their relationship with their creator. In their language there is no specific word for nature – it is linked directly to their reality. For the Mbyá, ‘nature’ is everything from spirituality to vital sustenance. The tree, honey or a bird are all manifestations of Ñanderu; nature and their creator are the same.

The ‘ychy’ is the traditional makeup of the Mbyá Guaraní. It is also used in rituals and to indicate milestones in daily life, in this case, the start of menstruation. Ychy is an ink paste of jata'i beeswax mixed with ash.

Shared memory and knowledge is sacred and fundamental in Mbyá Guaraní communities, through which it remains alive and latent. It is transmitted across the generations by the teachings of the elders; their world is collective, shared and communal.

The fruits of the jungle are a fundamental food source for the animals that inhabit them, as well as the Mbyá Guaraní communities. Everything in nature is a living manifestation of Ñanderu, the creator, and everything is shared and collected in a responsible way.

The evocation of collective memory allows the acquired knowledge of the Mbyá people to survive. They perceive the world and inhabit it according to the teachings of the community’s elders, chiefs and spiritual leaders (‘opygya’), who pass on everything that their creator, Ñanderu, taught them.